From the June 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

The black-and-white photograph shows a wood-panelled room with a pitched roof of dark redwood beams. A low table is pushed cosily up against a large brick hearth, and around it several children sit in easy chairs, one reading, others busily engaged in craft activities. At a piano, a girl strokes a cat, while a dog basks in the sunlight that slants across a large rug. This peaceful scene is the San Francisco living room of the artist Ruth Asawa (1926–2013), photographed in 1969. Asawa is nowhere to be seen, but her art is everywhere. Most conspicuous are the hanging wire sculptures for which Asawa is best known. Resembling elaborate lanterns or lighting fixtures, or biomorphic models of seed-pods or chrysalises, or complex fishing nets, or baskets, these sculptures fill the darkened space beneath the high rafters with miasmic, playful movement, catching the light as it filters through the window.

The living room of Ruth Asawa’s home in the Noe Valley neighbourhood of San Francisco, photographed by Rondal Partridge in 1969. Photo: © 2025 Rondal Partridge Archive

Close scrutiny of the photograph, however, reveals a much fuller picture of Asawa’s output than is often recognised. In the immediate foreground, a wooden surface (actually the top of a second piano, out-of-tune and unplayed) is crowded with white clay sculptures, including animals, flowers, faces, fantastical figures and a small pot. Many of these were made by Asawa’s children; the artist used an inexpensive mix of flour, water and salt to make ‘baker’s clay’, a medium she would sometimes cast into bronze, as she did for several well-loved (though critically scorned) commissions of public sculpture.

Despite the predominance of her abstract, meditative, woven sculptures, Asawa built her world around people, family and sociality. Her earliest training was as a teacher and, a year before this photograph was taken, she helped launch the Alvarado School Arts Workshop at her children’s school; the programme bringing artists into the classroom would expand to reach more than 50 schools. Asawa was generous and pragmatic – an approach that she may have acquired while studying at the progressive, pan-disciplinary Black Mountain College in the 1940s – and far from the purist that her most famous work might suggest. She had scant regard for binaries, but instead conjoined craft and fine art, tradition and modernity, functionality and uselessness, individualism and collaboration, figuration and abstraction, daily life and creativity.

Installation view of ‘Ruth Asawa: Retrospective’ at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 2025. Photo: Don Ross; courtesy David Zwirner; © 2025 Ruth Asawa Lanier, Inc.

Evidence of Asawa’s generosity and imagination fills a retrospective of the artist at San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA), which opened on 5 April and will travel later this year to MoMA in New York, then on to the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao and the Fondation Beyeler in Switzerland. Along with this celebration of her art and a re-evaluation of her contribution to the story of Western modernism comes a significant widening of the scholarship and understanding of Asawa’s life and work.

Untitled (S.363, Freestanding Basket) (c. 1948), Ruth Asawa. Asheville Art Museum. Photo: Christie’s; courtesy David Zwirner; © Ruth Asawa Lanier, Inc.

Asawa died in 2013, at the age of 87. Despite having been included in the 1959 show ‘Recent Sculpture U.S.A.’ at MoMA in New York, and having had a retrospective of her work in San Francisco in 1973, she was never widely known outside the latter city. She spent much of the 1970s and ’80s focusing on public sculpture and arts education, and sold her work infrequently. Then, in 2008, Asawa’s daughter contacted Christie’s to discuss the sale of a painting by Asawa’s old friend and teacher, Josef Albers, in order to raise money for her healthcare. Jonathan Laib, a specialist at Christies, saw Asawa’s work and, in 2010, oversaw the sale of one of her sculptures that went for $578,500, more than three times its high estimate. Three years later, just months before her death, both Christie’s and Sotheby’s sold works by Asawa for over $1 million. In 2017, Laib began working at David Zwirner, bringing to the gallery representation of Asawa’s estate. Her wire sculptures now regularly fetch $4m–$6m.

It’s easy to see why these elegant and original pieces are so beloved by collectors. But this wide-ranging retrospective and its thick and deeply researched catalogue are full of titbits that illuminate Asawa’s uneven career path and her bohemian life. For instance: that cat in the photograph, purring on the little girl’s lap, did not belong to the Asawa family, but had presumably just wandered into their home, where the tall, carved front doors were reportedly usually open. Four of those children are not Asawa’s, but their friends. (Asawa, with her husband, Albert Lanier, did indeed have six children, but only the youngest two are pictured here.) The especially comfy patterned armchair was known as the ‘peace chair’. On the piano sits a model of this very room, built by Asawa’s young son, for which she contributed a tiny version of one of her hanging sculptures, woven specially from fine-gauge wire. (In later life, she made several such miniatures, a case of which is installed at SFMOMA.) Asawa usually hung her large-scale sculptures, when she was working on them, from a hook under the lintel of the door between this room and the kitchen-dining room beyond, a convenient spot from where she could keep an eye on dinner.

The living-room photograph itself appears in the retrospective, dramatically enlarged to immersive proportions and forming the centrepiece of a wood-panelled gallery designed to recall Asawa’s home. There are her hanging wire sculptures, some of which can be identified in the photo; the most impressive of these is Untitled (S.039, Hanging Five Spiraling Columns of Open Windows) (c. 1959–60), a convoluted construction more than two metres tall comprising a sequence of unfurling apertures, rather than the enclosed lobes of other sculptures. Those twin front doors, which Asawa carved from redwood planks in 1961 with help from her kids, are installed nearby. There are several of the fired clay life-masks that Asawa liked to make of her friends and family, which she hung on a cedar-shingled outside wall. There are artworks by Asawa’s contemporaries, including stoneware bowls by Marguerite Wildenhain, with whom Asawa had shown in a 1954 exhibition at the San Francisco Museum of Art titled ‘Four Artist-Craftsmen’. (The designation of ‘craft’, used pejoratively, would follow Asawa throughout her career, to her indifference.) There is a geometric watercolour from 1947 by Albers inscribed to her. There are clay bead necklaces, made by Asawa in the 1980s and fired by her son Paul in a pit on a nearby beach. And there are bronze casts of Asawa’s tiny, industrious hands, originally made in wax in 1974 and then cast into metal five years after her death.

Asawa was born in Norwalk, south-east of Los Angeles, today incorporated as a city but in 1926 little more than a patchwork of farms. Asawa’s Japanese immigrant parents leased their small farm, since California’s Alien Land Law barred them from ownership, and their seven children went to work in the fields each day after school. The family had horses and chickens, and grew beans, tomatoes, onions, daikon and other crops. In early 1942, weeks after Japan attacked the US fleet in Pearl Harbor, FBI agents visited the farm and arrested Asawa’s father, who was incarcerated in camps in New Mexico until after the war. Two months later, just as the strawberries were ripening, the rest of the family was ordered to report to the Santa Anita detention facility east of Los Angeles, a former racetrack converted into rudimentary accommodation which they shared with more than 18,000 other detainees.

Japanese American Internment Memorial (PC.011) , designed by Ruth Asawa in 1990–94, stands outside the Robert Peckham Federal Building in San José. Photo: Laurence Cuneo; courtesy David Zwirner; © Ruth Asawa Lanier, Inc.

Half a century later, Asawa returned to those traumatic adolescent experiences while designing a major public art commission for the federal courthouse in San José, California, which commemorated the US government’s incarceration of more than 120,000 people of Japanese descent during the Second World War. A two-sided relief mural, cast in bronze but originally sculpted in baker’s clay, narrated the arrival of immigrants from Japan in the United States, their settlement and work on farms, their displacement and hurried abandonment of their homes and the grim conditions inside the camps. Asawa drew heavily on her own life, including a poignant scene in which her father set fire to the family’s traditional Japanese possessions, including books and a doll, in order to erase evidence of his heritage.

The folksy, illustrational style of the Japanese Internment Memorial (1990–94) is, like other of Asawa’s public commissions, awkward to correlate with her abstract work. It is not even a case of an evolving (or devolving) aesthetic; as early as the late 1960s she was designing large-scale figurative sculptures, such as her mermaid fountain, Andrea (1966–68), for the city’s Ghirardelli Square, while separately developing her elegant, abstract vocabulary of natural forms in wire and bronze, which she continued throughout her life. Andrea consists of two mermaid figures – cast from the torso of Asawa’s friend Andrea Jepson – surrounded by turtles and frogs on lily pads. Asawa spoke of her ambition ‘to make a sculpture that could be enjoyed by everyone’. Lawrence Halprin, the modernist landscape architect redeveloping Ghirardelli Square at that time, hated the fountain – which he described, not unreasonably, as ‘corny’ and ‘high camp’. Two of the contributors to the SFMOMA catalogue, Jennie Yoon and Marci Kwon, attempt a defence, pointing to Asawa’s use of her wire-weaving technique to sculpt the mermaids’ tails, her ‘rejoinder to the essentialism of categorisation’. Maybe. But there’s no doubt that such populist public sculptures pose a problem for historians of Asawa’s oeuvre.

Untitled (BMC. 56, Dancers) (c. 1948–49), Ruth Asawa. Private collection. Courtesy David Zwirner; © Ruth Asawa Lanier, Inc.

To fully understand the inconvenient variety of Asawa’s work, it is helpful to reflect on the lifelong influence of her early art education. In 1943, she was permitted to leave the internment camp in Arkansas where her family had been held, in order to enrol at Milwaukee State Teachers College. Due to rife anti-Japanese sentiment, the college refused to find her a practice placement, effectively preventing her from graduating. The sister of a classmate, however, told her of a radical, residential liberal arts college in North Carolina. In 1946, Asawa applied and was accepted into Black Mountain College.

At Black Mountain, students were required to grow and cook their own food and to participate in construction projects. Asawa the resourceful farm girl took to life at the college with zeal. She learned drawing, colour theory, design, mathematics, philosophy and music. She also studied dance in the summer of 1948 with choreographer Merce Cunningham. Asawa became close with the architect Buckminster Fuller, who designed her wedding ring: a silver cage holding a round, black river stone. Influential, too, was the teaching and friendship of German exiles Josef and Anni Albers, who had lost their jobs at the Bauhaus when it was forced to close by the Nazi party. Josef taught a compulsory design class at Black Mountain, in which he asked students to experiment with folding paper and bending wire; Anni taught weaving.

It was in a market in Toluca, west of Mexico City, that Asawa first saw egg baskets woven in wire, and learned from a local teacher how to loop and join the wire without the need for needles or hooks. Back in North Carolina, she practised the technique and soon was able to create voluminous, sturdy but flexible forms. The earliest wire pieces in Asawa’s retrospective are a plump basket and an oval platter, both made in 1948; while she was simultaneously creating colourful, abstract paintings in oil and watercolour, these woven pieces appeared more like traditional craft wares than avant-garde painting.

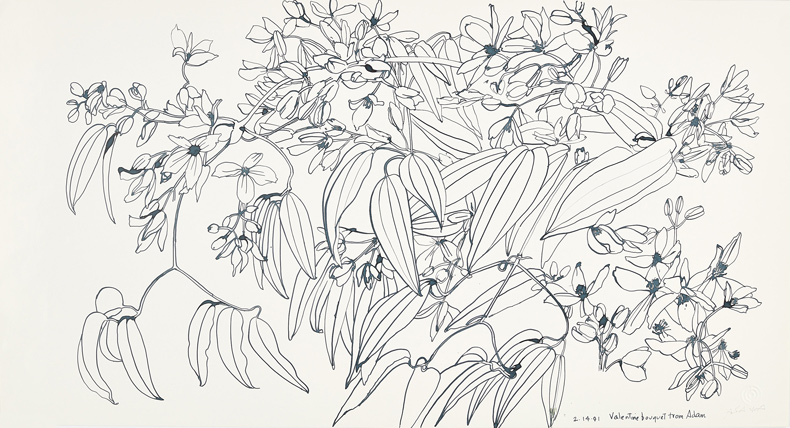

Valentine Bouquet from Adam (PF.555) (1991), Ruth Asawa. Private collection. Photo: James Paonessa; courtesy David Zwirner; © Ruth Asawa Lanier, Inc.

‘Nature is my teacher,’ Asawa later wrote. At Black Mountain, she met and fell in love with Albert Lanier, an architect who shared her fascination with botany. When, in 1948, Lanier moved to San Francisco to embark on his architecture career, Asawa followed and, in 1949, only months after California repealed its anti-miscegenation laws, the couple were married. In their various successive homes in San Francisco the couple cultivated thriving gardens, and Asawa studied their plants and flowers in careful pen drawings and watercolours. Generosity underpinned Asawa’s art: if someone gifted her a bouquet, she would often draw the flowers and present the drawing to the friend in exchange. In 1962, a friend brought her a dried plant specimen from Death Valley, which she found impossible to draw. Instead, she tied bundles of wire together into soft-edged, organic forms – a technique that blossomed into its own body of abstract sculpture.

Meanwhile, her hanging, woven sculptures became increasingly elaborate and complex, usually involving successive volumes inside one another or, in some instances, magically intersecting. She acknowledged their mind-boggling complexity in a hanging piece, UNTITLED (S.428, Hanging Möbius Strip) (c. 1960), a manifestation of the famous mathematical model which joins interior and exterior to create one continuous surface with a single edge. In the 1950s, when she undertook commercial design projects, she had devised a circular logo, an emblem she held dear throughout her life. This ‘Continuous Form within a Form’, as she called it, consists of looping concentric rings. Asawa’s looped-wire sculptures were always made with a continuous surface: two dimensions woven into three. In this regard, they encapsulate Asawa’s philosophy, as improbable syntheses of oppositional qualities. But they were only part of her story. As this exhibition shows, to tell one part without the other would be a disservice to the rich variety of Asawa’s long and irrepressible life.

Untitled (S. 428, Hanging Möbius Strip) (c. 1960), Ruth Asawa. Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, Bethany. Photo: James Paonessa; courtesy David Zwirner; © Ruth Asawa Lanier, Inc.

‘Ruth Asawa: Retrospective’ is at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art until 2 September, before travelling to other venues.

From the June 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](https://src.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Apollo at 100