This year’s edition of the Smithsonian Design Triennial, ‘Making Home’, which is currently on show at the Cooper Hewitt in New York, is rooted firmly in the conventional ideas of what a home is – at least on the ground floor, though each room takes the idea further than the average homeowner might consider possible. A number of artists have created installations that explore what is at stake in these interiors. Living Room (2024), Hugh Hayden, Davóne Tines and Zack Winokur’s recreation of what the museum calls ‘a slice of Virginia country life’, is a living room set on a giant rocker to the sound of a woman humming, sizzling bacon and the playing of a cello. It is at once monumental and precarious, a suggestion of what lies behind memories of home. In the room that once served as Andrew Carnegie’s study is Game Room, where artist Tommy Mishima has carefully drawn out the networks of Carnegie’s money and how it funded research, philanthropy and financial projects, the effects of which are still felt today. As fascinating and rich as these drawings are, it is impossible to walk into this room and not first be struck by the neon-coloured chairs that seem to be growing into a new life, a reconfigured form of mycelium that, like the influence of Carnegie’s money, is still growing and spreading in unexpected ways. These are by New York designer Liam Lee, whose work I first saw, also in New York, at the Noguchi Museum, when the Loewe Foundation took it over for the 2023 edition of the Loewe Foundation Craft Prize.

This goes some way to explaining the importance of what the Loewe Foundation has achieved with the Craft Prize, which is now in its eighth year. The prize was set up to support and celebrate craft as distinct from art; in other words, the artistry is as much about technique as it is about concept. The word craft means different things to different people. Loewe has found a way of defining it and celebrating some of the finest craft practitioners with its selection of 30 finalists each year.

Kyo (2024), Mikio Ishiguro. Courtesy Loewe Foundation; © the artist

This year’s exhibition at the Thyssen-Bornemissza in Madrid (until 29 June) is one of the best in recent years. While the coil pot by the winner, Kunimasa Aoki, shows the jury’s predilection for virtuosity over function, there are several works in this selection that show how designers can push their techniques to the limits of feasibility and still deliver something functional and fascinating.

Mikio Ishiguro’s Kyo (2024), made entirely from a paste of fallen leaves, naturally hints at decay and sustainability but could also be read as a textile sculpture, an updating of a felt work by Joseph Beuys perhaps. Or it could be seen as a responsive material whose shape and rigidity alter according to the humidity of the room.

Traditional techniques pushed to contemporary forms are a regular feature of the Loewe Craft Prize. The boldest example of this might be seen in Yeunhee Ryu’s beautiful curved lidded box made from hammered copper and silver solder. A few sheets of oxidised copper became an object of beauty and preciousness in Ryu’s hands.

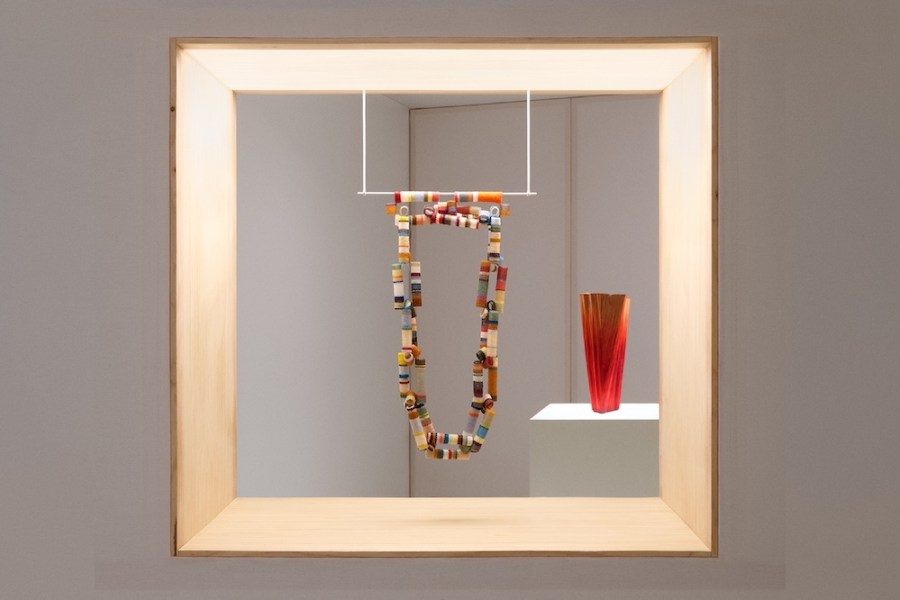

Pleats Vase No.7 (2024), Didi Ng. Courtesy Loewe Foundation; © the artist

One of the most extraordinary works was Didi Ng’s Pleats Vase No.7 (2024), in which 20 pieces of wood were joined together and the softer wood brushed away to create the appearance of fragility that is more familiar from porcelain vases. The dramatic red ink used to stain the wood emphasised its form, making it impossible to ignore.

For me, the work that stood out the most was by Studio Sumakshi Singh. Monument (2024) received a special mention from the judges, along with Nifemi Marcus-Bello’s TM Bench with Bowl (2023). Whereas Marcus-Bello’s work has already become part of the collection at LACMA and MoMA, for example, Sumakshi Singh’s work is not yet in any permanent collections. Monument is a life-sized embroidery in copper and nylon of a column from the 12th-century Qutab Minar complex in Delhi. The work is done on a water-soluble fabric that is then washed away leaving only the copper, looking like a shadow or ghost of the column, unable to support itself but hanging from the ceiling. The piece has a fragile beauty that brings to mind questions of how monuments function and how history is memorialised. For Singh, who made the work with a studio of embroiderers, Monument also foregrounds a technique that is often dismissed as women’s work, as opposed to the more physically demanding labour of weaving with machines. Yet in this piece, the embroidery is all that there is, each thread glistening with questions and ideas that deal with knotty questions of inheritance. Perhaps Loewe is right when it suggests that this is the future of craft – no doubt it will be coming to a design biennial soon.

Monument (2024; detail), Studio Sumakshi Singh. Courtesy Loewe Foundation; © the artist

The Loewe Foundation Craft Prize exhibition is at the Thyssen-Bornemisza National Museum, Madrid, until 29 June.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](https://src.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

‘Like landscape, his objects seem to breathe’: Gordon Baldwin (1932–2025)