From the June 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

You don’t have to enjoy cooking to find significance in kitchen tools. Utensils have long been valued for their symbolism even by those who have never dirtied their hands at the stove. A case in point is Elizabeth I. There is a series of portraits – created by a number of artists between 1579 and 1590 – in which the queen holds a kitchen sieve. Elizabeth’s sieve is a humble thing (unlike the dagger held by her father, Henry VIII, in his Holbein portraits), made not from precious metals but from a cheap brass-coloured metal called latten. It would be like the current King having his portrait done holding a blender.

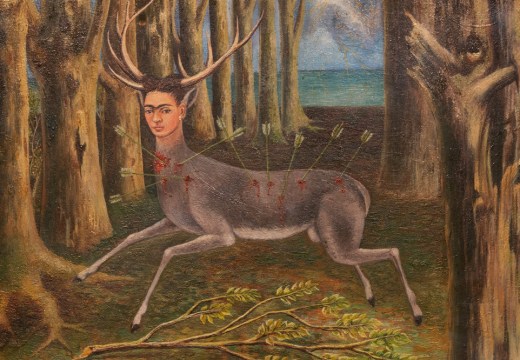

The best of Elizabeth’s sieve portraits is the one in the national art museum in Siena by the Flemish artist Quentin Metsys the Younger in 1583. Behind the queen we glimpse some male courtiers. At the front of the group, two courtiers with well-shaped calves in red and yellow stockings stare intensely into each other’s eyes. Behind them is another man in less colourful attire with the badge of a white hind (a female deer) on his cloak. The queen, dressed in austere black, pays no attention to this scene behind her as she delicately fingers her sieve.

In Tudor households, sieves were far more essential than they are today. In conjunction with a pestle and mortar, sieves performed many of the jobs for which a modern cook might use an electric food processor. Judging from her rich dress and aloof demeanour, Elizabeth is not planning to use her sieve for any kind of labour. The purpose of her sieve is symbolic. But of what?

Going back to ancient times, sieves have been associated with wisdom, which is easy enough to understand. Sieves are tools for sorting wanted items from unwanted ones. In Renaissance iconography, the figure of Prudence (one of the four cardinal virtues) carried a sieve to underline her ability to sift good from evil. On the edge of the sieve in Elizabeth’s Siena portrait there is a motto that translates as ‘Down goes the good and the bad remains in the saddle.’ Elizabeth is reminding her subjects that she is the arbiter of right and wrong; the sieve is a symbol of power disguised as a humble utensil.

Elizabeth I (1583), Quentin Metsys the Younger. Musei Nazionali di Siena. Courtesy Italian Ministry of Culture – Foto Archivo Musei Nazionali di Siena

Yet sieves also had another meaning: they were a well-worn motif for chastity, which is odd given that sieves are riddled with holes. The link goes back to a Roman story told about one of the Vestal Virgins, Tuccia, who was charged with ‘the crime of unchastity’. She prayed to the goddess Vesta and then filled a sieve with water from the River Tiber. She carried it all the way back to the temple without spilling a drop. And thus her chastity was proved!

It isn’t hard to see why this idea might have appealed to Elizabeth, the Virgin Queen. Throughout her reign she enhanced her authority with the notion that she had rejected worldly love in favour of her stately duties (while dangling the idea that she might marry, whether for the sake of a useful alliance or to produce an heir). The backdrop to the Siena Sieve Portrait was that it looked for a while as if she might finally give in to marriage. From 1579 to 1581, Elizabeth was being actively courted by François, Duke of Anjou.

Among members of the queen’s court, her possible marriage to the French nobleman was controversial. One of those in the anti-marriage camp was Christopher Hatton, a courtier who almost certainly commissioned the Siena portrait. Hatton is thought to be the shadowy figure in the background with the hind on his cloak. Perhaps the men in the colourful stockings are scheming to marry the queen off and he is coming to stop them.

When you know that Hatton was probably the painting’s patron, it takes on new connotations. Many observers (including Mary, Queen of Scots) said that he was Elizabeth’s lover. She was known to have admired Hatton’s dancing. Thanks to the queen’s favours, Hatton grew so wealthy that he was able to build the largest privately owned house in England. This fact alone suggests that he had the queen’s heart.

Then there is the brooch on the queen’s dress, which went almost unremarked until 2014 when two art historians, Christine Slottved Kimbriel and Henrietta McBurney, analysed it. It displays a naked man and woman, touching hands. At the base is the head of a ram (in letters between them, Hatton called himself the queen’s ‘sheep’). The sexiness of the brooch is at odds with the queen’s all-encompassing black dress, and may have been a very ‘deliberate and personal’ comment by Hatton about his relationship with the queen.

Public chastity could be a veil for private love. Assuming that Hatton and the queen were lovers – not that we will ever know – the sieve could be not only a public declaration of purity but also a coded love token. Maybe the yellow metal sieve that the queen is fingering so pensively is, among other things, a giant golden ring, an absurdly oversized gesture of love from Hatton to his royal mistress.

From the June 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](https://src.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Apollo at 100