From the June 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

In the Navarra region of Spain, just over the Pyrenees from France, lies Bodega Otazu – the northernmost vineyard with the highest quality rating in the Spanish appellation system. It sits at a cross-roads between centuries of French and Spanish traditions of viticultural exchange. The winery – built in 1840 in Bordelais chateau style – is 8km out of Pamplona, only 60km fromthe Bay of Biscay and 35km from the Pyrenees. More recently, its geographical advantages have been supplemented by a display of contemporary art. Guillermo Penso, the bodega’s owner, has scattered his collection throughout the grounds, cellar and working areas of the winery. Wine and art ‘are both cultural products, they both tell messages, they’re both reflections of their own time,’ he says.

Navarra is now landlocked, but the medieval kingdom of Navarre once stretched along Spain’s northern coast and over the Pyrenees towards Bordeaux. Its winemaking tradition was started by Cistercian monks in the 12th century. Records show that Carlos III ‘El Noble’, king of Navarre from 1387–1425, drank wines produced in Otazu. The region sat on the pilgrim route, the Camino de Santiago de Compostela and pilgrims also spread Navarra rosado (rosé), turning it into a popular trade commodity.

Navarra’s openness to trade made it one of the earliest wine regions in Spain to be ravaged by phylloxera in the late 19th century. This destructive pest destroyed the region’s vineyards, wiping out 99 per cent of the wine production in 1891–96. It never fully bounced back and today only 10,500 hectares of vineyards remain, with just 110 hectares in Pamplona, all belonging to Bodega Otazu.

View of Tools + Fire (2010) by Jim Dine at Bodega Otazu. Photo: Bodega Otazu

The Spanish-Venezuelan Penso family bought Otazu in 1994. At the time it was a 250-hectare farm without vines; under the stewardship of Guillermo, regenerative and vinicultural development had elevated Otazu by 2009 to the status of Vino de Pago. This is the most exclusive classification in the Spanish system, awarded to just a few wineries – at present, 19 of them; Otazu was the seventh. Pago wines are produced by a single vineyard, which is awarded the distinction in recognition of unique microclimatic conditions and soil characteristics, resulting in wines that maintain a high quality over time and age well. Otazu’s entire wine range is made with grape varieties grown in this single-estate vineyard – Tempranillo, Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Cabernet Franc, Pinot Noir, Chardonnay and Berués de Huarte.

The working parts of the winery are underground: the spectacular barrel cellar, known as the ‘La Catedral del Vino’, is dominated by a 14th-century press that resembles an altar; the first wine produced, in 1999, was named the ‘Altar’ in its honour. Above ground, the estate contains the 12th-century Romanesque church of San Esteban, which features a 16th-century altarpiece in the ‘plateresque’ style, a 14th-century tower and the 16th-century Palace of Otazu, now the family residence.

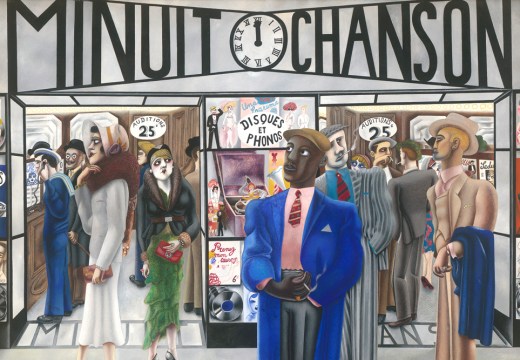

A family friend, the Venezuelan artist Carlos Cruz-Diez, who died in 2019, convinced the family to formalise its connection to the arts: ‘Tell them you’ve got this plot of land in between a 12th-century cathedral and a 14th-century pigeon tower and ask them what they could do with the place.’ To display the art, Penso initiated a biennial competition for the best work of monumental art. The work is spread throughout the grounds and includes the water and glass work The Colour of Our Lives (2015) by Alfredo Jaar; the musical installation Valkyries of Otazu (2017) by Leandro Erlich and the sculptural works Tools + Fire by Jim Dine (2010) and Au Soleil by Baltasar Lobo (1988)

As Penso says, ‘We buy the works, not the artists.’ The family displays only about 10 per cent of the 2,000-strong collection, which includes work by Tomás Saraceno, Rashid Johnson, David Magán and Ai Weiwei, but the art is regularly rotated. Art and wine are connected for Penso because they ‘both cater to human craving and search for human soul’.

View of Au Soleil (1988) by Baltasar Lobo at Bodega Otazu. Photo: © Bodega Otazu

The winery produces one of Navarra’s most expensive wines, the Vitral de Otazu, made from Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot. Each grape is carefully selected in a manual harvest, guaranteeing superior quality; then the grapes are destemmed by hand and undergo cold maceration followed by fermentation for 15 days in 225-litre French oak barrels, which are rotated six times a day. They are then macerated again for three weeks and pressed, before undergoing secondary malolactic fermentation in barrels for two months at 15°C.

The artist Manolo Valdés believes that these ‘wines are endowed with unlimited personality’. His label for this wine was inspired by his sculpture Ariadna (2007). Ariadne was abandoned by Theseus on Naxos after helping him to escape from Crete, and was discovered there by Dionysus, the god of wine and revelry, who fell in love and took her as his wife. She became immortal and a constellation as a result of their union, and gave birth to a son called Oenopion (oinos being the Greek for wine).

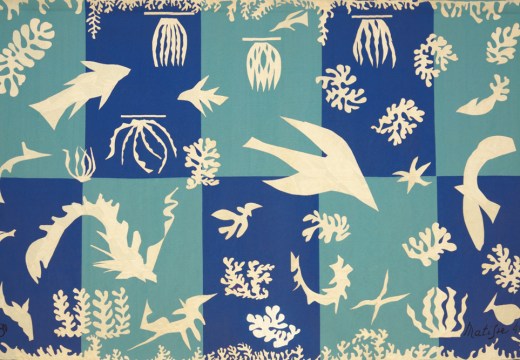

The most ambitious artistic connection to Vitral wine is the collaboration with Carlos Cruz-Diez, who created 30 specially designed labels for vintages – one for each year running from 2013 to 2042 – in a project he called Otazu Chromointerferences. Each bottle or group of bottles comes in a case and the 30 cases can be assembled as a sculpture, stacked, restacked, ensuring myriad possibilities for experiencing the artist’s work. This was a fitting way to honour ‘the Maestro’ Cruz-Diez, but also makes the connection between art and wine even closer. As Pensa says, ‘Let’s give people a great piece of art you can drink.’

From the June 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](https://src.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

‘Like landscape, his objects seem to breathe’: Gordon Baldwin (1932–2025)